Not all running feels the same. Recall the wind sprints of death you had to do in high school and compare that to the light jog you did yesterday to hurry across the street. And if you’re a runner, you know easy jogs feel completely different than the speedwork you have to do. Easy runs are aerobic-dominant and hard runs are more anaerobic. But when it comes to the 26.2-mile marathon, which is it?

Are marathons aerobic or anaerobic? Marathons are a mostly aerobic exercise (close to 100%, but not quite) because it requires sustained running for a long period of time. Marathons take anywhere from 2 – 6+ hours, so in order to complete one, you must run at a pace you can hold for a long period, which falls in the aerobic category.

But, it’s a whole lot more complicated than that. And if you’re not careful (perhaps you go out to fast) your anaerobic system will kick in too soon which could sabotage your marathon. In order to better understand why marathons are aerobic and how to keep them in that zone, let’s start with a bit of background on how the two zones differ.

Aerobic vs. Anaerobic Exercise

In order to have an understanding of which category marathon running falls into, you first need to know what aerobic and anaerobic actually mean. Then we’ll get more into why marathons fall much more towards the aerobic end of the spectrum.

Both aerobic and anaerobic exercise have their place in building a healthy cardiovascular system and a strong body.

What is aerobic exercise?

Aerobic exercise is completed at a level where your body continues to have enough oxygen for a sustained period of time, even with an uptick in your heart rate.

Any exercise that gets your heart rate up that you can sustain for a length of time would be considered aerobic.

Even though you’re working out, your breathing will remain even and you shouldn’t have to slow down to catch your breath. Walking briskly, jogging, swimming laps or doing the elliptical machine all fall into this category.

Aerobic exercise uses a combination of fat, protein, and carbs for fuel.

What is anaerobic exercise?

Aerobic exercise gets your heart beating very quickly. It won’t take long to feel out of breath and you get that lung burning feeling. Sprints, cycling hard to the top of a hill, jumping rope, and lifting heavy weights fall into this category.

Think of anaerobic exercise as anything that’s done at (or very close to) your max effort. It hurts!

Exercises that fall into the anaerobic category can be sustained for only a short period of time before you need to stop or slow down significantly to level your breathing.

Anaerobic exercise relies solely on glycogen (carb) stores for fuel.

Aerobic Vs. Anaerobic Running

So let’s narrow it down to running specifically. With all those different types of runs you do, where do they fall?

Aerobic Running

Runs that are truly aerobic are completed at an easy pace for an extended period. This may only be 10 minutes for a new runner, or hours for someone more experienced. You may also hear people refer to them as conversational or comfortable paced runs.

Aerobic runs are characterized by:

- lower heart rate (close to 70% of your max heart rate)

- low intensity

- low waste product build up (you don’t feel like you have to stop to catch your breath)

Don’t mistake “easy” aerobic running as unnecessary or as junk miles. It’s quite the opposite. As I write about in my article, “Train Slower to Run a Faster Marathon,” 75 – 80% of your runs should be completed at an easy pace. They are extremely important for building endurance and the extent of time you can run aerobically.

Anaerobic Running

Anaerobic runs are generally the speed work you might see on your schedule. You can hold your anaerobic pace anywhere from 30 seconds to 10 minutes depending on your level of fitness.

For most runners it’s a love/hate relationship with these types of runs…they are exciting yet intimidating and sometimes leave you feeling like you might throw up at the end. Fun, right?! But then once that feeling goes away you might finding yourself when you can do that again. No one ever said runners weren’t weirdos.

Anaerobic running is characterized as:

- uncomfortable

- high intensity

- a pace that’s difficult to hold over an extended period of time

- feeling the need to slow down

- high waste product build-up (like CO2)

I like how Healthline outlines this type of running: your oxygen demand surpasses your oxygen supply. You can literally feel this as it happens – and you’re not just making up that “I can’t breathe” feeling. So what do you do? You drop your pace way down, or you stop. And it’s amazing how quickly that breath comes back when you do so.

Is all running either/or?

No. And to make it even more confusing, there is also the lactate threshold, which is a zone sitting between aerobic and anaerobic. According to Runners Connect:

“The lactate threshold is the point at which lactic acid is just beginning to accumulate while the anaerobic threshold describes the point at which lactic acid builds faster than the body is able to remove it, usually occurring at about 4 mmol/L of lactate.”

Tempo runs (done at a pace you could sustain for up to 60 minutes) fall into this category. And even then you’re still going to be in the aerobic an anaerobic zones for a period of time. More on that.

Utilizing Both the Aerobic and Anaerobic Zone When You Run

Because rarely is anything as simple as black and white, the truth is that all the running you do essentially uses both systems. It’s the percentages of each that make different kinds of runs feel so different.

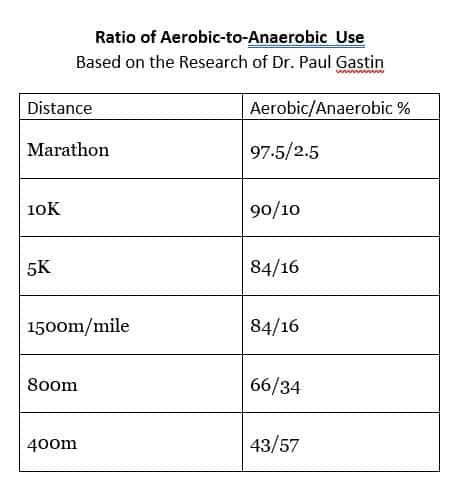

This chart gives a good estimate of the time spent in each zone for different typical running distances.

Topping the list is the marathon. Using the approximation that 97.5% of a marathoner’s miles are spent in the aerobic zone, let’s do a bit of quick math (and by quick I mean I used my calculator):

26.22 miles x .975 = 25.56 in the aerobic zone

So, less than 2 miles in the anaerobic zone. Let’s talk about it.

Why Marathons are Mostly Aerobic (and a Bit Anaerobic, too)

So we now know that the marathon is a race completed almost entirely in the aerobic zone. Or at least it should be.

Going back to what we learned about aerobic exercise and aerobic running, let’s answer the question, “Why is marathon running aerobic?“

1.) In order to appropriately run a marathon, you need to get to the pace you can hold steady for the majority of the race, ideally almost the whole time (much tougher than it sounds!)

2.) True marathon pace keeps your intake of oxygen and elimination of waste products in balance.

You may run 8:15 one mile, and 8:25 the next and keep the miles coming in that range. That small difference likely won’t take you out of your aerobic zone, provided that’s the pace you’ve trained for. And of course, you have to account for hills because maintaining an even effort means slower on the uphills and faster on the downhills.

But can there be too much anaerobic and not enough aerobic?

Yes. And that’s not good. Let’s say I want to smash my marathon PR so I decide to go out at 7:45s when I’ve trained for 8:10s. I’ll be able to hold that pace for many miles, perhaps even 13, but definitely could not even come close to 20+. I’d get into the anaerobic zone way too soon and need to slow down significantly to get back to an aerobic state.

Crossing over into anaerobic territory (or even sooner at lactate threshold we talked about) would sabotage my race.

Bottom line: Even though 1.5 -2 miles spent in the anaerobic zone won’t be the exact number for every person, it’s a good rule of thumb. Learning to get the pacing just right so you don’t get there too soon will maximize your performance.

If you get into that oxygen-depleted state too soon, your marathon race will suffer. So save it til the final push, mile 24+, then give it all you’ve got.

If marathons are more aerobic, why do I hit the wall?

After hearing this tidbit of information and you’re thinking about a past marathon where you completely hit the wall, I’m guessing it’s becoming a lot more crystal clear.

Even though a marathon SHOULD be mostly aerobic, that doesn’t mean it ends up that way. And if it doesn’t, your pace will slow drastically in the late miles of your race.

Hitting the wall in a marathon is generally attributed to these three factors:

- lack of proper training (not enough mileage)

- depletion of glycogen stores

- going out too fast in the marathon

What’s talked about less often if when you crossover to an anaerobic zone, it can really be hard to come back from. And that feels a lot like bonking or hitting the wall.

Outside Online shares the following information that explains how declining critical power (think fatigue) and anaerobic capacity also play a role:

“Even if you down carbohydrates, your critical speed is almost certain to drift downward late in a marathon. When that happens, you either have to slow down, or you’ll start drawing on your anaerobic capacity.”

The Real reason marathoners hit the wall in the marathon

Ultimately, late in a marathon, you may even be running at what’s typically your easy pace but functioning at close to your max heart rate. Even though your pace doesn’t seem like it, all the other factors combined have led you to that anaerobic state. And that can make for a very long slog to the finish line.

How to Stay in the Aerobic Zone for the Marathon

One major point to make is that when you race a marathon, you’re NOT running at your easy pace. For example, my easy pace is between 9:10 – 9:30, but my marathon pace averages around 8:20.

Though running your marathon race at an easy pace would likely solve your problem of hitting the wall, most people want more than that. In order to keep the ratio of aerobic to anaerobic rate close to the 97.5/2.5 percentages this is what you need to focus on:

1.) Run more miles in training. That means start your training weeks sooner (here I talk about why 20 weeks is ideal) so you can safely build to proper peak mileage. For me that’s right around 60 miles, but it’s different for everyone. Aim for at least one peak week of 50 miles.

READ: Want to be Prepared for Your Marathon? Run More Miles

2.) Run 75 – 80% of your mileage at an easy pace and in the aerobic zone. There is a time and a place for speedwork or tempo runs that move you out of that aerobic zone, but the majority of your runs should be conversational paced. This will strengthen your cardiovascular system by becoming more efficient at circulating oxygen through your body, and prepare you to make marathon goal pace your aerobic pace on race day.

READ: Train Slower to Run a Faster Marathon

3.) Focus on pacing in your marathon. Always start conservatively. In a marathon, there is PLENTY of time to make up the difference later on if you feel good. Here we learned that anaerobic running relies solely on glycogen. And depleting those stores too soon makes the end of a marathon very challenging. Fellrnr.com writes, “glycogen usage varies nonlinearly with pace.” For example, if you run an 8:00 pace one mile, and 8:30 the next, you will use more glycogen than running two miles at 8:15. This is why practicing marathon pace in training is so important (and then sticking to it in the race!)

READ: Why Banking Time in Your Marathon is a Bad Idea

Of course if you have more left to give those last few miles of the marathon, do it! I will tell you from experience that it’s much more fun getting near the end of those 26.2 miles feeling like you have more to give than walking the last 6 miles because you were ill-prepared or didn’t pace well.

Just remind yourself that crossing over into that anaerobic zone, even just for a minute, is not worth it! Your best marathon will be one that’s done almost entirely in the aerobic zone.